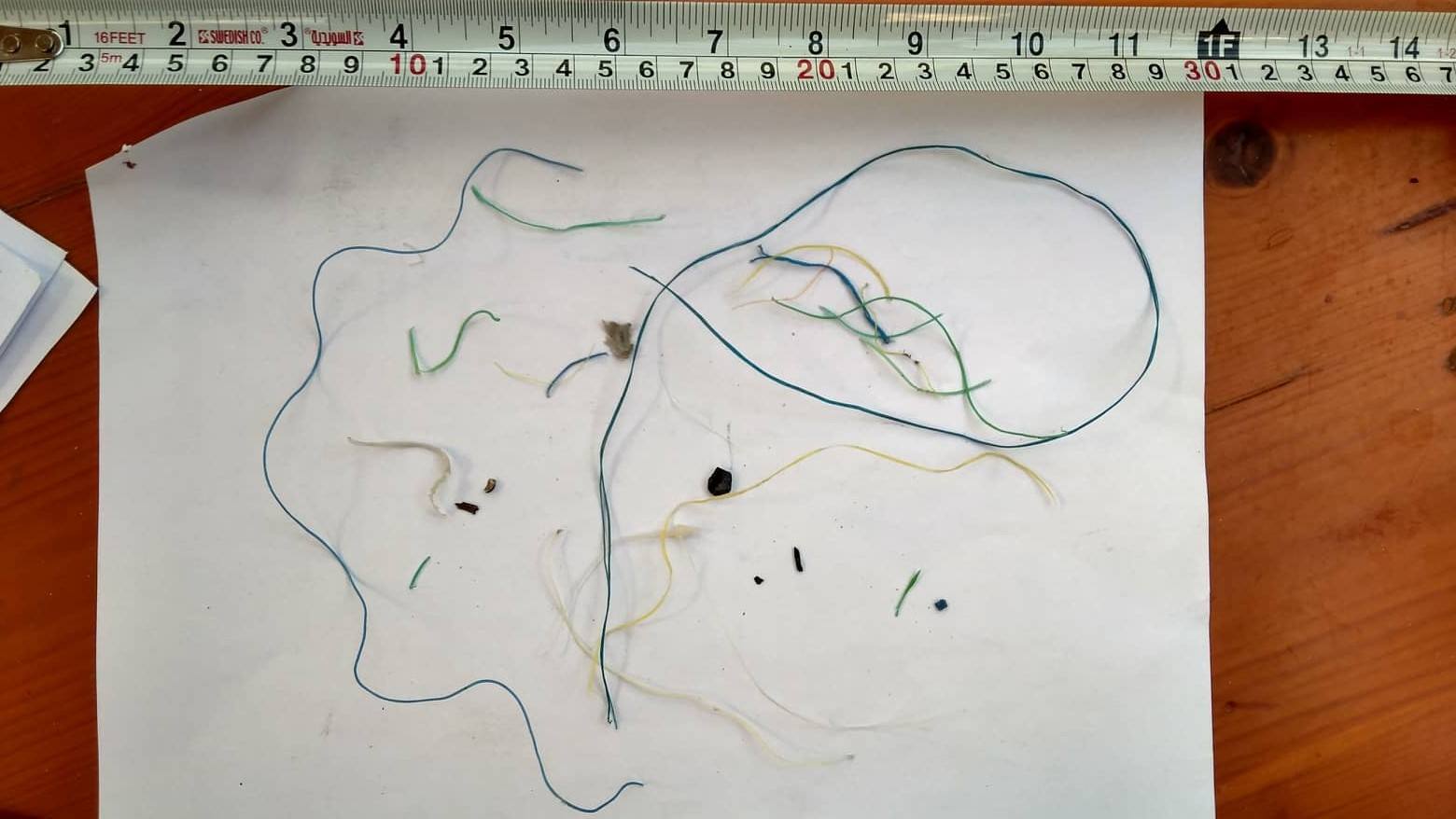

The publication today of an article in Nature Geoscience about the presence of airborne microplastics on an isolated and otherwise pristine mountain in the Pyrenees will inevitably make the news. Although it is not the first time that we have been made aware of microplastics in the air we breathe, it does add another piece to an atmospheric transportation jigsaw puzzle about which we know very little. The research is extremely sound with analysis of microplastics characteristics being undertaken by RAMAN spectroscopy. The paper also reaches some solid conclusions, although it might be argued that the incidence of microplastics is somehow related that wind speed, precipitation and wind direction might be an obvious one. Similarly the isolation of the location would by definition mean that sources have to be from some distance away. But, perhaps the questions it really raises is should we be surprised or worried at all about the incidence of microplastics in these pristine areas?

Plastics and microplastics in particular, are pervasive, pernicious and persistent. They do not ‘fit’ in the natural environment and consequently for that reason alone we should be concerned. However, perhaps of more significant concern at this time is what we don’t know. There is a significant disparity between the amount of plastics we produce and the amount we recycle, or have identified in the environment.

Speaking at the EGU last week, Richard Lampitt from the National Oceanography Centre, highlighted this lack of knowledge, pointing out we can only account for 10% of the total plastic we put into the oceans every year. We don’t know where it is, neither do we even partially understand the impact it will have on the oceans ecosystems. We know that the potential impacts of endocrine disrupting toxins inherent within, or carried by microplastics have a detrimental effect on human health, but we don’t know by to what extent, or how it will necessarily manifest itself in the future. Similarly, we don’t know the long term implications of ingesting, or inhaling microplastics, but it would be fair to say they are unlikely to be beneficial.

The implications of this and other research like it, is that we only know that we now live in a world infested by plastics. Whilst it has changed our lives for the better in many ways, it has a more insidious side, one that we were previously unaware of. One recurring theme of the last two hundred years has been the introduction and development of products and processes without fully understanding what the long term implications might be.

The fact is that we should be worried, but not necessarily by what we know, such as the specifics of airborne microplastics in the Pyrenees, but by what we don’t know. It is inevitable that wherever we look we will find microplastics and it is something that we will never be able to clear up – all we can do is to try and prevent the problem becoming worse. However, while we do this it is equally imperative that we take the implications of this and other research into microplastics seriously. We need to invest in science in order to fill in our knowledge gaps. I would encourage people to look at potential worst case scenarios and work towards them, rather than assume ‘it will all work out alright. This report, like all of the others, is a warning and we have to try and look into the future if we are to prevent what is currently a problem from becoming a predicament. You only have to look at the litany of our past environmental and health catastrophes to understand why.