Fast Fashion

You may not realise it, but the clothes you are wearing could inadvertently be causing harm to the ocean environment. The fashion industry is actually one of the biggest contributors of microplastics into the ocean and it is also responsible for huge amounts of carbon getting into the atmosphere. Did you know for example that pollution from the fashion industry has contributed to a 76% decline in average freshwater fish populations worldwide.

The problem is an industry business model called ‘Fast Fashion’ which has been evolving since the 1980’s. It involves quick turnarounds with lower prices, rapid reactions to new styles and increased numbers of new fashion collection. Fast fashion business models entice over consumption, the production of cheap low quality clothes and excessive waste.

100 Billion clothes a year for just 7 billion people

- Clothing production is the third biggest manufacturing industry after the automotive and technology industries.

- Textile production contributes more to climate change than international aviation and shipping combined

- It is calculated that more than $500 billion of value is lost every year due to clothing underutilisation and the lack of recycling.

- In the UK, WRAP estimates that £140 million worth of clothing goes to landfill every year.

- (House of Common Environmental Audit Committee, 2019)

- “The fashion industry is responsible for 8% of carbon emissions” (UN Environment, 2019)

- Around 35% of materials in the supply chain end up as waste.

We are literally eating drinking and breathing our clothes – a few facts

- Approximately 20% of global freshwater pollution is caused by the fashion industry.

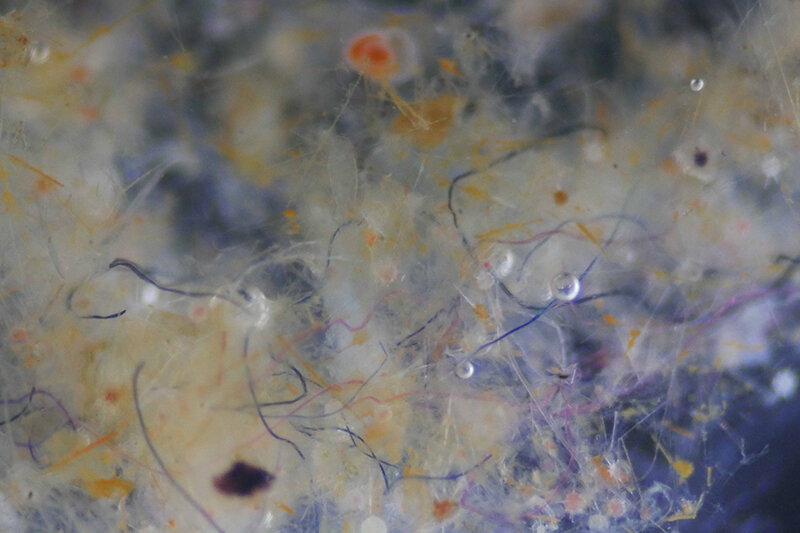

- When manufactured, washed, worn, and disposed of, synthetic clothes release plastic microfibers that pose risks to animal and human health in the environment.

- Synthetic fibres are being found in the deep sea, in Arctic sea ice, in fish and shellfish.

- Because textile fibres travel all over the world by air and by water there is a constant fall-out of microfibres.

- Fashion accounts for 20 to 35% of all the microplastic that flows into the ocean.

(The State of Fashion, McKinsey 2020) - When ingested microplastic fibres can cause serious harm to fish including aneurysms, respiratory problems and excessive egg production.

What are the Solutions?

Slow Fashion

- Slow fashion is the opposite of fast fashion. It encompasses an awareness and approach to fashion that considers the processes and resources required to make it. Slow fashion advocates for buying better-quality garments that will last longer, and values fair treatment of people, animals, and the use of the planets recourses.

- Some characteristics of a slow fashion brand include:

- Made from high quality, sustainable materials like linen

- Garments are more timeless than trendy

- Often sold in smaller (local) stores rather than huge chain enterprises

- Locally sourced, produced, and sold garments

- Few, specific styles per collection, which are released twice or maximum three times per year, or a permanent seasonless collection

- Often made-to-order to reduce unnecessary production

A Circular Business Model

- A system of a rent-based closed-loop supply could be developed to improve the sustainability of fashion products. Providing services such as maintenance, recycling, reverse logistics and final waste disposal.

- Circular fashion is a system where our clothing and personal belongings are produced through a more considered model: where the production of an item and the end of its life are equally as important. This system considers materials and production thoughtfully, emphasising the value of utilising a product right to the end, then going one step further and re-purposing it into something else. The focus is on the longevity and life cycle of our possessions, including designing out waste and pollution.

Change how you wash

- Hand wash or use a shorter washing cycle at a lower temperature or ‘eco’ mode. The longer the wash, the more time for microplastics to be released. Wash similar textiles together. Fibres can be released as tougher fabrics rub up against softer ones.

- Reduce friction between clothes by doing full washes rather than half full washes, as less space allows less friction. Use liquid detergent instead of powder and ensure lint filters are thrown in the trash rather than down the sink.

- The Cora Ball is a pinecone-esque laundry ball that catches microfibres in the wash; the LINT Luv-R is a filter that attaches to the washing machine outflow, and a Guppy bag is a self-cleaning fabric bag made of a specially designed micro-filter material that you wash your clothes in.

What can retailer do about it?

- 1. Move away from the fossil-fashion business model: Establish a concrete, accountable and time-bound plan to move away from the unsustainable fast-fashion model, and reduce reliance on synthetic materials, through a viable trajectory and targets for the uptake of more sustainable alternatives. Prioritise phasing out synthetic fibres from children’s clothing and collections for new mothers, as there is emerging scientific evidence that young children’s health is the most vulnerable to microfibre pollution.

- 2. Commit to ambitious and comprehensive climate targets: Set ambitious commitments to rapidly move supply chain away from coal and other fossil fuels by 2030, to achieve the minimum 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, scientists warn is needed to stay within a 1.5 degree pathway. These should cover all supply-chain emissions, including factories and mills, transportation, raw-material cultivation and endof-life disposal. Climate strategy must also include transitioning away from fossil fuel-based fabrics (see point 1).

- 3. Invest in true circularity: This should include higher durability of garments, longer warranties, offering repairs to customers and promoting reuse. Instead of promoting recycled materials produced from PET bottles or ocean plastic, invest in viable and environmentally benign fibre-to-fibre recycling technologies. Ensure, too, that any toxic chemicals are eliminated in the design process, as these might get recycled back into new clothes, harming the health of your customers.

- 4. Ensure any green claims made are not false or deceptive: Claims must be clear and unambiguous. Do not omit important and relevant information (for example, on the product’s end of life); ensure comparisons made are fair and meaningful, and that claims are substantiated and easily accessible to consumers. Stop making unsubstantiated claims on the recyclability of garments sold, in the absence of any viable fibre-to-fibre recycling technology.

- 5. Provide full, publicly accessible and transparent information on your suppliers: Including all the factories and supply-chain stages from which textiles are sourced –not just ‘tier 1’ and ‘tier 2’ factories.

- 6. Openly support progressive legislation to improve circularity and transparency in the industry (for example, mandatory EPR schemes), encourage peers to do the same and leave any industry initiatives that oppose, delay or undermine progressive legislation – including its implementation.

Useful Reference Sources

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

http://changingmarkets.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/SyntheticsAnonymous_FinalWeb.pdf

https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/210322TNCBain_Pre-ConsumerMicrofiberEmissionsv6.pdf

https://assets.ctfassets.net/fsquhe7zbn68/4MQ9y89yx4KeyHv9Svynyq/8434de64585e9d2cfbcd3c46627c7a4a/Research_MicrofibersReport_191004-e.pdf

Adidas, Nike, H&M and Zara products tested on microfiber loss during washing