A couple of months ago we were contacted by the BBC Victoria Derbyshire show about a programme they were planning regarding microplastics. This is an area we are currently researching so we were happy to oblige. As a result we spent a cold windy day on a South coast beach with a couple of students from Loughborough looking for microplastics by using the sampling method from our Big Microplastic Survey Project. The area tested was heavily contaminated with pre-production pellets (nurdles) as well as secondary microplastics, not that unusual along this stretch of coastline. The results from that survey are still being analysed and will be put into our database in due course but one of the images below shows how much was found in 0.25 sq m of sediment.

A couple of months ago we were contacted by the BBC Victoria Derbyshire show about a programme they were planning regarding microplastics. This is an area we are currently researching so we were happy to oblige. As a result we spent a cold windy day on a South coast beach with a couple of students from Loughborough looking for microplastics by using the sampling method from our Big Microplastic Survey Project. The area tested was heavily contaminated with pre-production pellets (nurdles) as well as secondary microplastics, not that unusual along this stretch of coastline. The results from that survey are still being analysed and will be put into our database in due course but one of the images below shows how much was found in 0.25 sq m of sediment.

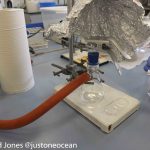

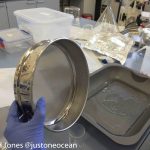

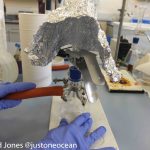

However, that was not all that the BBC were after; they wanted to know if there was microplastic in our tap water. We suspected that there would be as previous research had identified ‘anthropogenic debris’ in tap water previously, but nothing had been done in the UK as far as we were aware. We were sent tap water samples from 14 different locations around the country. Each had been prepared in the same way and was delivered in an identical bottle. We also tested control samples using the same bottles and simulated the transportation process. Each sample was filtered through a fine 38 micron sieve before then being run through a 0.2 micron filter and stained with Nile Red. The results were not what we were expecting.

Using a blue light the non-organic material on the filters fluoresces under a microscope making it possible to count the ‘fibres’ and ‘pieces’. When we examined the control samples of ultrapure MilliQ water we found a total of between 40 to 60 microparticles per litre providing us with an indication of ‘background’ contamination. However, our tap water samples were double and in some cases triple that number. In one location 203 particles were found in 1 litre of water. This Nile Red test could not categorically state that the particles were plastic, only that they were likely to be inorganic and further analysis was required. To achieve this we tested more samples without staining and prepared the micro particles for examination under an FT-IR scanner.

Using a blue light the non-organic material on the filters fluoresces under a microscope making it possible to count the ‘fibres’ and ‘pieces’. When we examined the control samples of ultrapure MilliQ water we found a total of between 40 to 60 microparticles per litre providing us with an indication of ‘background’ contamination. However, our tap water samples were double and in some cases triple that number. In one location 203 particles were found in 1 litre of water. This Nile Red test could not categorically state that the particles were plastic, only that they were likely to be inorganic and further analysis was required. To achieve this we tested more samples without staining and prepared the micro particles for examination under an FT-IR scanner.

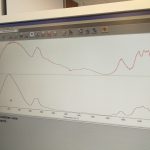

This FTIR process compares the material being tested with known databases and the results indicated a ‘match’ with cellophane and nylon. Due to a number of reasons, such as contamination of the material, the matches could not, once again be conclusively determined as plastics, but in the absence of any other matches the jigsaw puzzle was definitely starting to come together. Images of the ‘fibres’ can be seen in the gallery and we will leave you to make your mind up.

At the end of the day, given what we know about airborne plastic contamination and the never ending breakdown of plastics into smaller and smaller particles it is highly likely that microplastics are getting into the water we drink. The questions this raises are at which point in the supply chain is this happening, can we do anything about it and what are the long term implications likely to be to human health and the environment in general? Further research is in the pipline, if you will excuse the pun!

You can see the full programme here until end of March

- Conducting our own scientific research